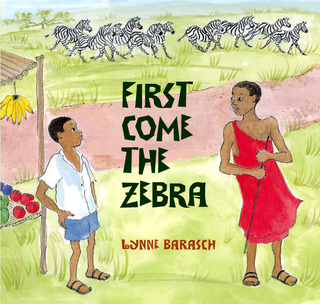

First Come The Zebra

REVIEWS

From School Library Journal

Grade 2–5—In Kenya, the Maasai are cattle herders and the more numerous Kikuyu are farmers. The two groups often fight about land use. This story uses that age-old conflict as a vehicle for contemplating enmity and friendship. When Abaani, a Maasai boy, sees young Haki's Kikuyu vegetable stall near his family's grazing land, he repeats what he's heard from his elders: "You destroy our land!" Haki, of course, takes offense, and the boys are ready to become enemies. However, they see one another's good qualities when circumstances force them together to rescue a straying toddler. Repeated exposure and a few good games of mancala finally bring about a mutual trust, and they take a real step toward peace when they decide to trade veggies for milk, and to introduce their families. A framing metaphor about the harmony between zebra, wildebeests, and the Thomson's gazelle gently reinforces the lesson. Heartfelt storytelling and strong research combine to offer a universal message with a unique setting. The clear, light-filled illustrations are expressive and create a sense of place. A lovely, hopeful story that manages to convey its message with minimal didacticism.

Paper Tigers

Lynne Barasch,

First Come the Zebra

Lee & Low Books, 2009.

Ages 6-11

An annual migration of African animals provides foundation and metaphor for award-winning author-illustrator Lynne Barasch’s tenth book. When the grasslands in Kenya are tall from the rain, “nearly two million animals will come from the vast savanna in neighboring Tanzania. The grass there has been grazed to the ground, so the animals migrate to Kenya, where there is plenty. They have done this for thousands of years.”

The zebra, wildebeest, and Thomson’s gazelle come in turn, each eating a few inches of the tall grass. “By sharing the land, there will be plenty for all. There will be peace among the grazers.” But there is not peace among the tribal peoples of Kenya. Tension persists between the farmers, the Kikuyu, and the cattle growers, the Maasai, as farms encroach on cattle grazing lands. When Abaani, a young Maasai, sees a Kikuyu boy tending a vegetable stall, he impulsively accuses him of “what he has heard others say,” of destroying the land. Haki, the Kikuyu boy, is equally indignant.

A crisis leads the boys to cooperate. Together, they rescue a baby who has wandered off from his mother into the territory of dangerous warthogs. After this incident, the boys slowly make friends with each other and eventually initiate some trading, milk for vegetables, with the hope that their families, too, may one day become friends.

Barasch’s superb watercolors depict Kenya’s wide savannahs, distinctive animals, and very human interactions. A double page of individual gazelles, leaping, nursing, feeding, and resting on bits of green gives a sense of both the vast and the particular in her story. A final illustration of the boys on the savannah at sunset, listening to distant hoofbeats that signal the start of another great migration, captures her optimism about peace among Kenya’s tribes. A map of the country is provided. An author’s note explains the traditional conflict between the Maasai and the Kikuyu and a game, mancala, that the boys play as they become friends.

Barasch has said that she finds hope in the youth of Kenya, who chat online about breaking down traditional tribal hostilities. In Abaani and Haki, she offers children appealing role models for making peace with neighbors and protecting their environment in the process.

Charlotte Richardson

October 2009